Why 1953 was Greenville's tipping point for segregation

Legendary Locals of Greenville by Cindy Landrum)

In 1953 this expansion of city government coincided with the introduction of the first color televisions on sale and the unveiling of the Corvette to the public as America’s answer to the status quo. Color was quickly becoming the City’s biggest challenge.

[caption id="attachment_3070" align="aligncenter" width="700"] In 1953 the Carolina Southern Railroad offered regular service in Greenville, SC. The influx of new residents and a growing sense of worldliness helped advance the fight against segregation. Greenville remains a major destination for families and individuals relocating to the South.[/caption]

Black Greenville was spirited and activist-minded long before 1953. Rural southerners were moving into Greenville to take jobs in the many textile mills thriving and growing, and the Greenville municipal government had been differentiating itself from other cities in the South by debating a progressive agenda to move beyond class stratification. Fieldcrest Village, Greenville’s first public housing project, opened in 1953, and there were efforts to provide better resources to offset the injustices of segregation by creating new public buildings and schools to serve the needs of citizens.

In 1953 the Carolina Southern Railroad offered regular service in Greenville, SC. The influx of new residents and a growing sense of worldliness helped advance the fight against segregation. Greenville remains a major destination for families and individuals relocating to the South.[/caption]

Black Greenville was spirited and activist-minded long before 1953. Rural southerners were moving into Greenville to take jobs in the many textile mills thriving and growing, and the Greenville municipal government had been differentiating itself from other cities in the South by debating a progressive agenda to move beyond class stratification. Fieldcrest Village, Greenville’s first public housing project, opened in 1953, and there were efforts to provide better resources to offset the injustices of segregation by creating new public buildings and schools to serve the needs of citizens.

But Mayor Cass wasn’t Greenville’s integrator. The city clawed at justice for blacks who were under-served and denied basic rights. But other city officials were concerned with social justice, and a growing class of educated locals would advance an atmosphere for change.

In 1953 Americans of color in Greenville were being heard. That year WFBC merged with WFBC to form the Southeastern Broadcasting Company (eventually becoming WYFF). The radio station hired Marie Bates, the first black woman to conduct a daily show. Her voice balanced the changing world and people were listening, both black and white.

The torch of justice burned even brighter when, in 1951, Donald Sampson became the first African American lawyer to practice in the city. For many years it was Sampson who defended the rights of the oppressed and helped defend the legal rights of blacks in Greenville. In 1953 the McBee Avenue branch library for blacks completed its first year in operation with Jeannette Smith organizing the efforts as head librarian.

But separate was not equal.

It was this McBee Avenue branch library for blacks that set into motion what would become the most pivotal moment for the march against segregation in Greenville’s library system. Spartanburg and Columbia already had integrated libraries. Greenville would be next.

Springfield Baptist Church, with leader Reverend James Hall, teamed up with New Pleasant Grove Baptist Church’s Reverend S.E. Kay to take a stand for equality in library services. These unsung heroes should be credited with one of America’s greatest acts of heroism in racial equality when Hall and Kay helped to organize the Greenville Main Library protest in 1960.

But Mayor Cass wasn’t Greenville’s integrator. The city clawed at justice for blacks who were under-served and denied basic rights. But other city officials were concerned with social justice, and a growing class of educated locals would advance an atmosphere for change.

In 1953 Americans of color in Greenville were being heard. That year WFBC merged with WFBC to form the Southeastern Broadcasting Company (eventually becoming WYFF). The radio station hired Marie Bates, the first black woman to conduct a daily show. Her voice balanced the changing world and people were listening, both black and white.

The torch of justice burned even brighter when, in 1951, Donald Sampson became the first African American lawyer to practice in the city. For many years it was Sampson who defended the rights of the oppressed and helped defend the legal rights of blacks in Greenville. In 1953 the McBee Avenue branch library for blacks completed its first year in operation with Jeannette Smith organizing the efforts as head librarian.

But separate was not equal.

It was this McBee Avenue branch library for blacks that set into motion what would become the most pivotal moment for the march against segregation in Greenville’s library system. Spartanburg and Columbia already had integrated libraries. Greenville would be next.

Springfield Baptist Church, with leader Reverend James Hall, teamed up with New Pleasant Grove Baptist Church’s Reverend S.E. Kay to take a stand for equality in library services. These unsung heroes should be credited with one of America’s greatest acts of heroism in racial equality when Hall and Kay helped to organize the Greenville Main Library protest in 1960.

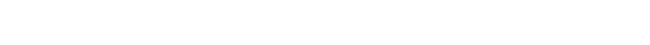

Five girls, led by 18-year old Hattie Smith and including Doris Walker, Dorothy Franks, Blanche Baker and Virginia Hurst, and two boys, Benjamin Downs and Robert Anderson, attempted to use the library. This time, they refused Stowe’s request to leave. The librarian, acting on instructions from Mayor Kenneth Cass, called the police. Four officers came to arrest the seven Sterling students. They took the youngsters to the Greenville jail, booked them on charges of disorderly behavior and placed them in cells, where the students began singing patriotic songs. Within half an hour, lawyer Donald Sampson, Rev. Hall, bail bondsman Tony Shelton and several reporters gathered. – from Integrating Greenville’s library in 1960 by Judith BainbridgeAfter a long legal battle exposed the deep differences in how citizens of Greenville felt about integration, the charges against the students were dismissed. [caption id="attachment_3071" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Residents at Perry Avenue in Greenville, SC in 1953. Today, Perry Avenue represents one of the most dynamic neighborhoods in Greenville’s West-end. [/caption]]]>

Residents at Perry Avenue in Greenville, SC in 1953. Today, Perry Avenue represents one of the most dynamic neighborhoods in Greenville’s West-end. [/caption]]]>