One white family's perspective on racism in Greenville, SC

West End where on a typical day he crossed railroad tracks to deliver News-Piedmont newspapers in Nicholtown before crossing back to visit a storefront where he read baseball scores to Joe Jackson. I was told a lot of stories about Greenville. Racism in Greenville, SC was not generally discussed in our family because segregation was so firmly ensconced in Greenville’s cultural fabric.

But the results of Jim Crow were obvious to my father as he collected money and conducted business throwing newspapers at the doors of all of Greenville’s classes. He canvassed the neighborhoods in this way from the age of nine until he graduated from Greenville High and went to Clemson College. “I could see the poverty,” he remembers. “But I’m telling you that the blacks paid their bills better than the whites on my route.”

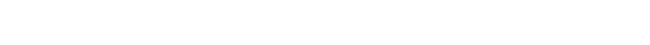

[caption id="attachment_2866" align="aligncenter" width="770"]

But the results of Jim Crow were obvious to my father as he collected money and conducted business throwing newspapers at the doors of all of Greenville’s classes. He canvassed the neighborhoods in this way from the age of nine until he graduated from Greenville High and went to Clemson College. “I could see the poverty,” he remembers. “But I’m telling you that the blacks paid their bills better than the whites on my route.”

[caption id="attachment_2866" align="aligncenter" width="770"] Delivering papers for the Greenville News kept Paul Wright, Jr. in all the best and the worst neighborhoods in Greenville, South Carolina.[/caption]

During my 20-years career penning articles and molding public relations campaigns, I stayed away from the prickly question of racism in Greenville, SC. Then I began apportioning time to learn about Greenville’s rich history of black and white families getting along as well as their division. I’ve heard a lot of stories about those who sought for harmony against the tide of segregation, but mostly from the perspective of my family and others among my businesses, neighborhoods and churches.

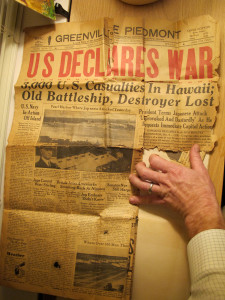

From his childhood home on Perry Avenue, my father thrived along with the textile town. The family was upwardly mobile living in a place with all the modern features of other big cities in the United States. My father and nearly everyone became more occupied with war than racism in Greenville, SC after the Japanese attacks. Perhaps an apologist might go so far to say that winning World War II in the way that we did helped push integration forward – the national unity was historic. But it took decades for racism in Greenville to really be addressed, and when it became an issue there was a feeling of intrusion by mainstream white Southerners. “We felt that the government was coming in and telling us what to do too much,” my father said. “We don’t like that here. We wanted to do it in our own good time.”

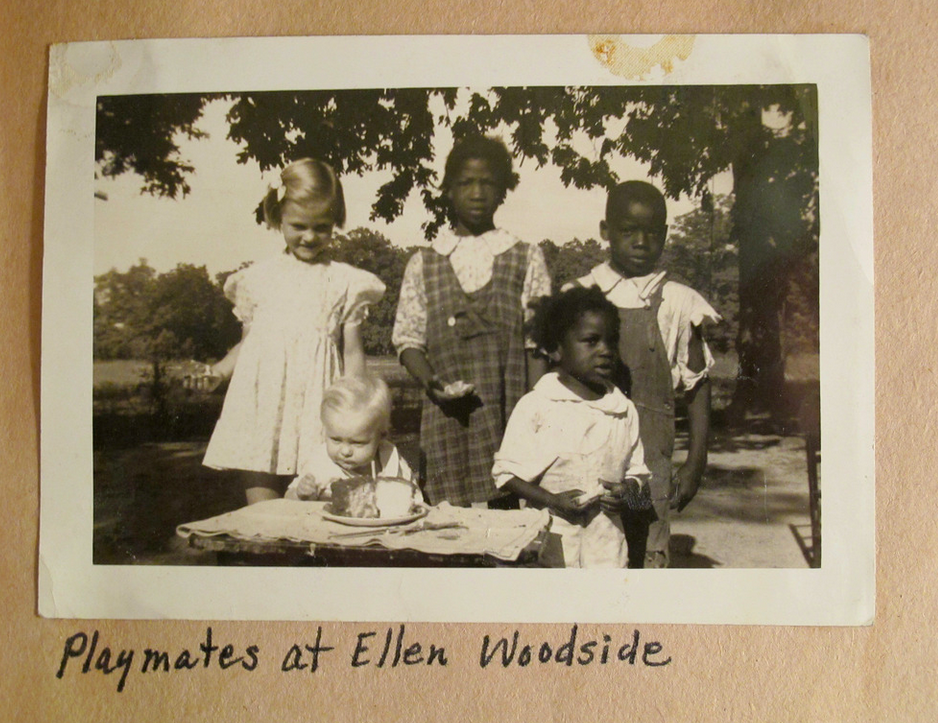

[caption id="attachment_2829" align="aligncenter" width="242"]

Delivering papers for the Greenville News kept Paul Wright, Jr. in all the best and the worst neighborhoods in Greenville, South Carolina.[/caption]

During my 20-years career penning articles and molding public relations campaigns, I stayed away from the prickly question of racism in Greenville, SC. Then I began apportioning time to learn about Greenville’s rich history of black and white families getting along as well as their division. I’ve heard a lot of stories about those who sought for harmony against the tide of segregation, but mostly from the perspective of my family and others among my businesses, neighborhoods and churches.

From his childhood home on Perry Avenue, my father thrived along with the textile town. The family was upwardly mobile living in a place with all the modern features of other big cities in the United States. My father and nearly everyone became more occupied with war than racism in Greenville, SC after the Japanese attacks. Perhaps an apologist might go so far to say that winning World War II in the way that we did helped push integration forward – the national unity was historic. But it took decades for racism in Greenville to really be addressed, and when it became an issue there was a feeling of intrusion by mainstream white Southerners. “We felt that the government was coming in and telling us what to do too much,” my father said. “We don’t like that here. We wanted to do it in our own good time.”

[caption id="attachment_2829" align="aligncenter" width="242"] Paul Wright, Jr. dressed for a war rally downtown Greenville, SC in approximately 1944.[/caption]

My dad was privileged where he was born in 1938, and the family lived as well as the other white middle-class families downtown. But World War II forced lessons in frugality and extended depression-era habits for everyone and in all classes. The circumstances brought out the best of Greenville, and it became a well-known triumph when Jews were helped to escape Hitler’s death camps with the help of Greenville citizens who sponsored escapes. (Max Heller, who escaped Vienna to Greenville, was both a Jew and one of the greatest Mayor’s Greenville has seen).

Dad told stories about the impact of the War on his childhood: the sparks from the tank tractors patrolling in anticipation of an invasion from Nazis and Japanese armies; the crash landing of a B-25 Mitchell medium twin-engine bomber being tested at Greenville Army Air Base in 1942; his uncle who was deployed and killed in a plane over Germany; and the thrill of V-Day where the nation united under the glory of liberation in Europe and the vanquished end to the Imperial Japanese Army.

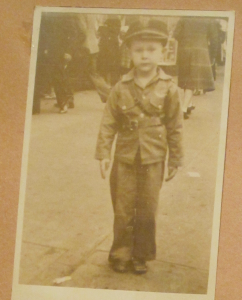

[caption id="attachment_2881" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

Paul Wright, Jr. dressed for a war rally downtown Greenville, SC in approximately 1944.[/caption]

My dad was privileged where he was born in 1938, and the family lived as well as the other white middle-class families downtown. But World War II forced lessons in frugality and extended depression-era habits for everyone and in all classes. The circumstances brought out the best of Greenville, and it became a well-known triumph when Jews were helped to escape Hitler’s death camps with the help of Greenville citizens who sponsored escapes. (Max Heller, who escaped Vienna to Greenville, was both a Jew and one of the greatest Mayor’s Greenville has seen).

Dad told stories about the impact of the War on his childhood: the sparks from the tank tractors patrolling in anticipation of an invasion from Nazis and Japanese armies; the crash landing of a B-25 Mitchell medium twin-engine bomber being tested at Greenville Army Air Base in 1942; his uncle who was deployed and killed in a plane over Germany; and the thrill of V-Day where the nation united under the glory of liberation in Europe and the vanquished end to the Imperial Japanese Army.

[caption id="attachment_2881" align="aligncenter" width="604"] World War II Ration Book from Greenville, South Carolina[/caption]

World War II Ration Book from Greenville, South Carolina[/caption]

He learned math on the backs of war ration books, and he was put to work by his father raising rabbits for meat.

My grandparents were teachers, Democrats and advocates for New Deal policies and were practically opposed to the pro-integration platform advanced by Roosevelt and his party. They were involved within the black communities as tutors and supporters decades before schools were integrated in Greenville. In letters and journals my family wrote in a vernacular off-putting to anyone not familiar with how the white class sometimes speaks about the other races, but their efforts should be seen as sincere for the time because they were actively combining other cultures of mid-century South Carolina with theirs. My white father swam together with black children during lakeside trips, and he went apple picking on at least a few occasions at a black church in North Carolina. [caption id="attachment_2880" align="aligncenter" width="225"] Greenville Newspaper announcing World War II.[/caption]

One picture culled from my dad’s baby book shows a disheartening depiction, nonetheless. My well-dressed father and aunt celebrate a birthday with black children dressed in rags. Gamamma said they knew school integration would come one day and they wanted it – but not yet. In her 80s she lived on Jones Avenue but at the age of 89 she finished her days in a nursing home in White Rock, SC where she reflected on how she thought about segregation after the war:

Greenville Newspaper announcing World War II.[/caption]

One picture culled from my dad’s baby book shows a disheartening depiction, nonetheless. My well-dressed father and aunt celebrate a birthday with black children dressed in rags. Gamamma said they knew school integration would come one day and they wanted it – but not yet. In her 80s she lived on Jones Avenue but at the age of 89 she finished her days in a nursing home in White Rock, SC where she reflected on how she thought about segregation after the war:

“It wouldn’t make any sense to either community because neither blacks nor whites would learn anything in the same classroom. We were catching the blacks up.”

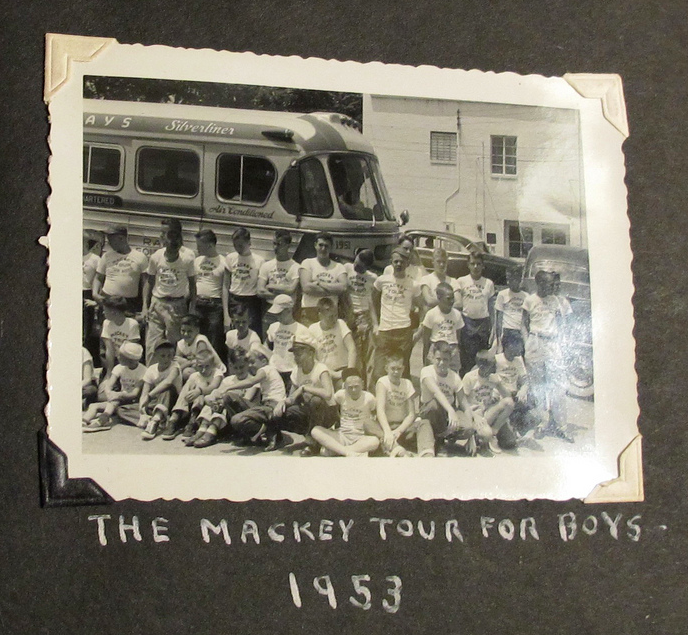

In fact, her view was one of the more liberal perspectives on the subject of combining schools in Greenville. Federal law mandated all Greenville County schools be integrated no later than 1970, and my grandparents were the teachers supporting its course, standing with the black kids who braved the first days in white schools. But it wasn’t easy and the vitriol from those opposing it was bitter. I think about if they could have done more to bring an end to so much separation and racism in Greenville sooner, but then I do believe they were doing the best they could. My dad went to Greenville High School and worked summers in various roles, bagging groceries and butchering at Lucky Food Store, soda jerking at F.W. Woolworth Company and baking bread at Claussen’s Bakery. His senior year he worked evenings helping to make textiles at Judson Mills. [caption id="attachment_2831" align="aligncenter" width="688"] The Mackey Tour bus arrived in Manhattan during a month-long trip beginning July 10, 1953 from Greenville, SC. Carol Campbell was one of many teens taking the trip.[/caption]

In 1953 he left Greenville on a bus packed with 16-year old’s headed for Canada. Mr. Mackey, the bus driver, lead the charge of the confederate bus northward. Among the load were childhood friends Carol Campbell and others who slept on the bus and in YMCAs during the 30-day journey covering all the major sites from North Carolina to Washington, DC to New York City and over the Maine border into Canada. A journal exists with my father’s observation on visiting so many places far from his home in Greenville, SC. “Nothing teaches tolerance like travel,” he always told me. My own childhood would be spent traveling just the same as he did.

There is a portion of my father’s diary devoted to going to Coney Island in New York City. The glitz and excess of the theme park was in full swing, but what he said about his trip out there and back speaks to the theme of experience and reconciliation.

The Mackey Tour bus arrived in Manhattan during a month-long trip beginning July 10, 1953 from Greenville, SC. Carol Campbell was one of many teens taking the trip.[/caption]

In 1953 he left Greenville on a bus packed with 16-year old’s headed for Canada. Mr. Mackey, the bus driver, lead the charge of the confederate bus northward. Among the load were childhood friends Carol Campbell and others who slept on the bus and in YMCAs during the 30-day journey covering all the major sites from North Carolina to Washington, DC to New York City and over the Maine border into Canada. A journal exists with my father’s observation on visiting so many places far from his home in Greenville, SC. “Nothing teaches tolerance like travel,” he always told me. My own childhood would be spent traveling just the same as he did.

There is a portion of my father’s diary devoted to going to Coney Island in New York City. The glitz and excess of the theme park was in full swing, but what he said about his trip out there and back speaks to the theme of experience and reconciliation.